File:Olive harvest in 2014, Palestine - Wikimedia Commons

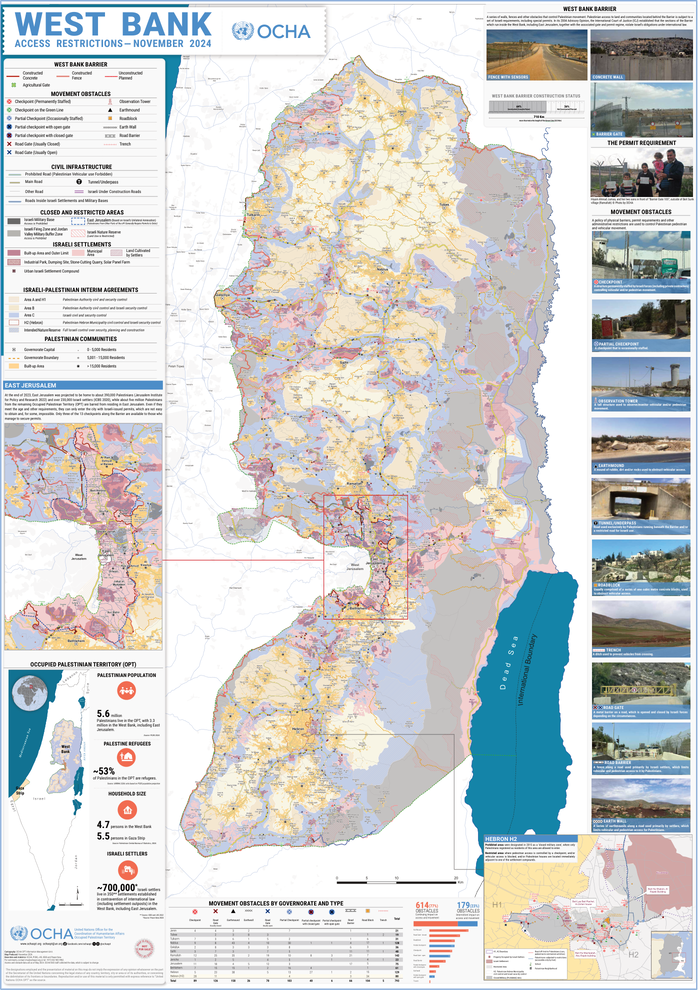

ISLAMABAD: The expansion of Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank has entirely reshaped the region’s geography, displacing thousands of Palestinians, further tightening control over land captured by Israel in the 1967 war.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), more than 12,000 Palestinian-owned structures, including 3,553 agricultural and 3,547 residential buildings, have been demolished or seized in the West Bank since 2009.

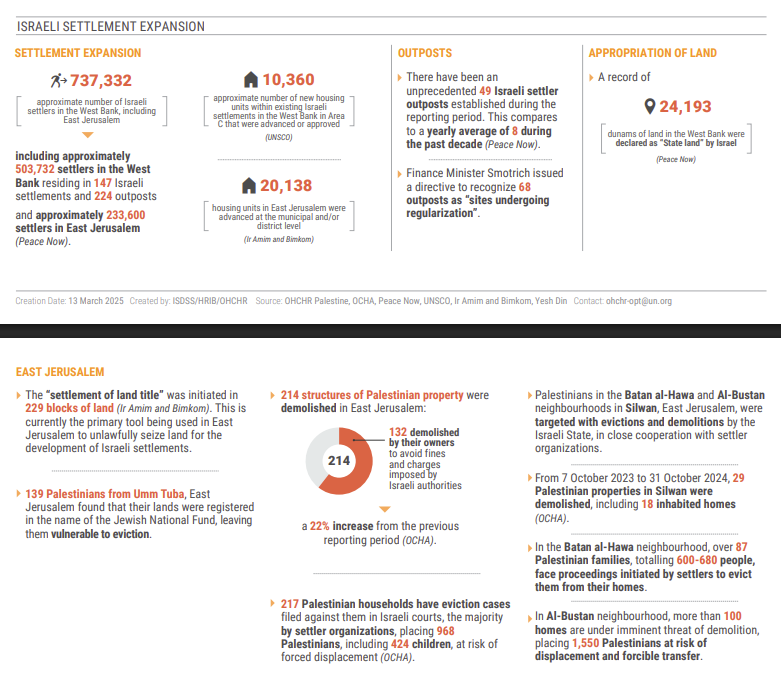

Reports indicate that over 700,000 settlers live among approximately 2.7 million Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Who are the West Bank settlers?

The term "settlers" refers to Israeli citizens who live in settlements or outposts established in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem.

The population is not homogeneous. Some settlers are motivated by religious or ideological beliefs, while others move for economic reasons such as affordable housing and access to infrastructure or strategic geography.

Many live in areas where Palestinian building permits are virtually unobtainable and land access for Palestinians is restricted.

According to the Palestinian Center for Human Rights, a younger, more ideological generation of settlers is increasingly encouraged by far-right political donors and government-backed organizations to establish new outposts or farms.

In the first quarter of 2023 alone, OCHA recorded 290 demolitions, displacing 413 Palestinians and disrupting the livelihoods of almost 11,000 individuals.

How do they occupy Palestinian land?

Settlement expansion in the West Bank operates through a combination of legal, administrative and coercive means.

Land is frequently declared “state land” or reclassified as a military firing zone or nature reserve, particularly in Area C, which remains under full Israeli military control. Once reclassified, Palestinian use of the land becomes prohibited, while settlers gain access for construction.

Another strategy is to establish outposts, which are small, unauthorised farming or residential communities constructed without government approval. These outposts are later retrospectively legalised, with the authorities providing electricity, roads, and security services.

According to OCHA and rights groups including B’Tselem and Yesh Din, settlers have repeatedly attacked Palestinian farmland, with incidents involving arson, vandalism and theft. In one case documented by B’Tselem, settlers from the Har Brakha area invaded olive groves near Burin, set fire to equipment and destroyed olive trees.

Why olive trees?

The pattern of expansion extends beyond homes. Olive groves, grazing pastures and water resources are systematically targeted.

A UN-rights office report found that in 2023 roughly 96,000 dunums of olive-groves remained unharvested due to access restrictions and violence, costing Palestinian farmers millions of dollars.

Olive cultivation is the economic and cultural foundation of Palestinian rural life. The destruction of these trees not only destroys livelihoods, but also weakens ancestral and symbolic ties to the land. Strategically, agricultural land near settlement routes or expansion corridors is the most vulnerable. Restricting access to these regions reduces Palestinian presence and increases displacement.

Do settlers have any legal rights to the land?

The United Nations, International Court of Justice (ICJ) and UN Security Council resolutions have repeatedly affirmed that settlements “have no legal validity and constitute a flagrant violation of international law.”

“Israel’s settlement policy, its acts of annexation, and related discriminatory measures are in breach of international law and violate Palestinians’ right to self-determination,” UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk stated earlier this year.

Israel, on the other hand, uses its domestic legal system to justify settlement actions, frequently defining land as "state property" or "closed military areas." Palestinians face significant legal and financial impediments when trying to contest these measures in Israeli courts.

Before and After: A pattern of displacement

Susiya, a village in the South Hebron Hills, exemplifies the long-term pattern. According to OCHA's 2015 factsheet, Susiya is a community "at imminent risk of forced displacement," citing recurrent demolitions and denial of infrastructure permits. Ten years later, demolition orders remain in effect, and settlement construction in the surrounding area continues.

UN data shows more than 20,000 settler housing units were advanced or approved in 2025 alone, marking one of the highest figures on record, with no end to expansion in sight.

Latest News

Iran, US talks to be held Friday in Oman: Iranian media

AN HOUR AGO

Gaza civil defense says death toll from Israeli strikes rose to 17

5 HOURS AGO

Putin tells Xi Moscow-Beijing alliance 'stabilizing' for world

5 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

Iran formally allows women to ride motorcycles

6 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

Ukraine delegation arrives in UAE for Russia talks

6 HOURS AGO