File: MetOp Second Generation A-type satellite (Wikimedia Commons)

ISLAMABAD: Pakistan on Monday urged the United Nations Security Council to develop legally binding international rules to regulate the rapidly growing number of satellites in outer space, warning that unchecked expansion in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) threatens digital equity, national sovereignty, and global security of developing countries.

Speaking at an informal Arria-Formula meeting of the 15-member Security Council in New York, Pakistani delegate Gul Qaiser Sarwani outlined a stark vision of a space economy increasingly dominated by a handful of wealthy nations and powerful corporations.

SpaceX’s Starlink constellation alone comprises approximately two-thirds of all active satellites, with more than 9,000 satellites currently in orbit (about 8,600 operational) and regulatory approval for up to roughly 12,000 additional satellites, according to the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

What is the problem?

Pakistan warned that the unregulated proliferation of LEO satellites risks exacerbating the global digital divide by privileging states with advanced technological and financial capabilities, while marginalizing others’ access to orbital resources and spectrum.

Pakistan's position is unequivocal: outer space, including LEO, is the province of all humankind, not subject to national appropriation or de facto control.

“Outer space is a global commons and must not become the exclusive domain of a few,” Sarwani said. “Technological or commercial dominance must not translate into exclusive access or regulatory advantage.”

Pakistan argued that the pace and scale of satellite expansion have outstripped existing international governance frameworks. While space is governed by treaties such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, these agreements were drafted decades before the rise of private space companies and do not impose enforceable limits on the number of satellites, traffic management, or data use.

Sarwani warned that the absence of binding rules risks creating ‘satellite congestion’ — overcrowding of orbital pathways that could increase collision risks and generate long-lasting space debris.

National sovereignty and militarization concerns

Pakistan also framed the issue as one of national sovereignty. Foreign-controlled satellite constellations operating over national territories, the delegation warned, could undermine states’ ability to regulate data flows, protect privacy, and safeguard sensitive infrastructure.

The use of satellite networks for surveillance, intelligence gatherin,g and information operations could heighten mistrust among states and exacerbate geopolitical tension. “Unregulated satellite activity risks eroding strategic stability,” Sarwani cautioned, adding that transparency and accountability were essential to prevent misperceptions and escalation.

Raising alarm over the growing militarization of space, Pakistan noted that the dual-use nature of many satellite technologies blurs the line between civilian and military applications. This, it warned, increases the risk of conflict and miscalculation, particularly as space-based assets become integral to modern warfare.

Are other countries pushing back?

Pakistan isn't alone in raising these concerns.

Several African countries have advocated for reconsidering the first-come, first-served principle, arguing that principles of equity and conservation should prevail.

Iran has similarly argued that existing regulations for orbital slots allocation have restricted the capacity of many countries, with many orbital slots occupied only by the most developed countries, leaving little chance for developing countries to place their own satellites on appropriate orbital slots.

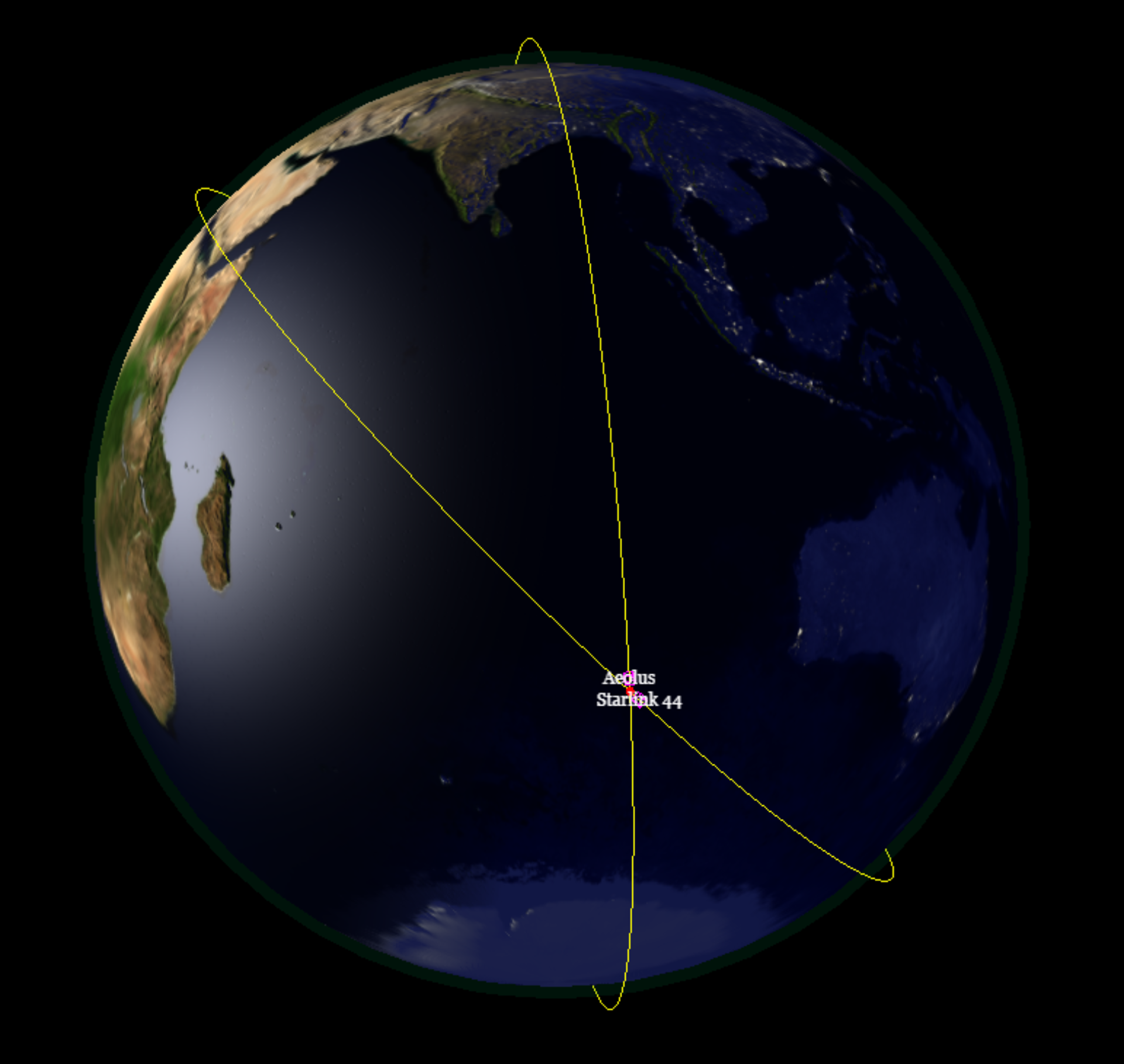

The European Space Agency has experienced the operational challenges firsthand. In 2019, ESA had to maneuver its Earth observation satellite to avoid a collision with a Starlink satellite. This incident highlighted how the rapid deployment of commercial constellations is creating coordination challenges even for established space agencies.

Predicted near miss between Aeolus and Starlink 44 (European Space Agency)

Predicted near miss between Aeolus and Starlink 44 (European Space Agency)

The solution

While many developing countries are pursuing national satellite programmes to reduce dependence — including Pakistan’s PakSat high-throughput satellite, Turkey’s TÜRKSAT-6A launched in 2024, and Brazil’s Amazônia-1 for environmental monitoring — Islamabad argued that national efforts alone are insufficient.

Pakistan urged the international community to move beyond voluntary guidelines and confidence-building measures, calling instead for a comprehensive, legally binding UN-led framework to govern satellite traffic management, ensure equitable access to orbital resources, and prevent the weaponization of outer space.

Latest News

Bangladesh to distribute 0.5M farmer cards in 180 days

31 MINUTES AGO

.jpg)

Iran president says ahead of US talks not seeking nuclear weapon 'at all'

AN HOUR AGO

US imposes 126% duty on Indian solar exports, raising trade concerns

2 HOURS AGO

Cuba kills four on US-registered speedboat trying to 'infiltrate'

5 HOURS AGO

Trump, Zelensky speak before Ukraine-US talks in Geneva

6 HOURS AGO

(1).png)