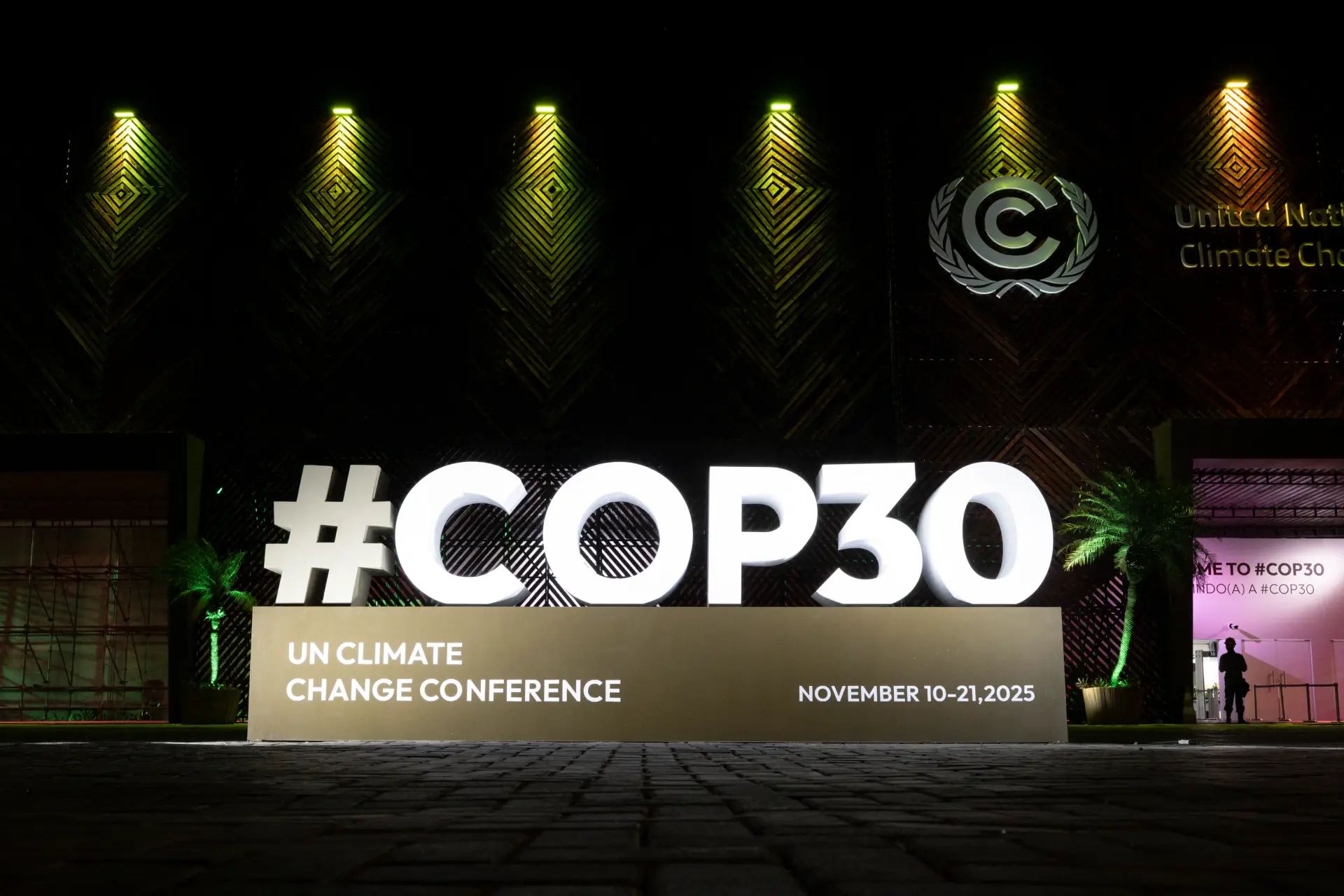

PARIS: This year's United Nations climate summit promises to be symbolic, marking a decade since the Paris Agreement and taking place in the environmentally vulnerable Amazon in Brazil from Nov. 10 to 21. But what is actually on the agenda?

The marathon negotiations gather nearly every country to confront a challenge that affects them all, but unlike recent editions, this “COP”, or Conference of the Parties, has no single theme or objective.

That does not mean big polluters will get off easily at COP30, with climate-vulnerable nations frustrated at their level of ambition and financial assistance to those most affected by a warming planet.

Here are the big issues to look out for as world leaders gather in the city of Belém, located at the mouth of the Amazon River, on Thursday and Friday before the start of formal negotiations the following week:

Emissions

The world is not cutting emissions fast enough to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, and no amount of pomp and pageantry at COP30 will sugarcoat that uncomfortable reality.

Under the climate accord, signatory nations are required to submit stronger targets every five years to cut greenhouse gas emissions, thereby steadily raising the collective effort to reduce global warming.

The latest round of pledges for 2035 was due in February, giving the UN time before COP30 to assess the quality of these commitments.

Most nations missed that deadline, but by early November, about 65 had turned in their revised plans. Few have impressed, and China’s target in particular has fallen well short of expectations.

The European Union, riven by infighting among member states, cannot agree on its target, while India, another major emitter, is yet to finalize its pledge.

A reckoning could be coming in Belem. Brazil — which described the latest round of pledges as “the vision of our shared future” — is facing pressure to marshal a response.

Money

Money — specifically, how much rich countries give poorer ones to adapt to climate change and shift to a low-carbon future — is a likely point of conflict in Belém, as it has been at past COPs.

Last year, after two weeks of acrimonious haggling, COP29 ended unhappily with developed nations agreeing to provide $300 billion a year in climate finance to developing ones by 2035, well below what is needed.

They also set a much less specific target of helping raise $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 from public and private sources. Developing nations will be demanding some actual detail about this at COP30.

Adaptation is a major focus of the summit, particularly a funding shortfall to assist vulnerable nations in protecting their people from climate impacts, such as building coastal defenses against rising seas.

Forests

Brazil chose to host COP30 in Belém because of its proximity to the Amazon, an ideal stage to draw the world’s attention to the rainforest's vital role in fighting climate change.

At COP30, the hosts will launch a new, innovative global fund that aims to reward countries with high tropical forest cover for keeping trees standing rather than chopping them down.

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) aims to raise $25 billion from sponsor countries and another $100 billion from the private sector, which will be invested in financial markets. Brazil has already contributed $1 billion.

Clement Helary from Greenpeace told AFP the TFFF “could be a step forward in protecting tropical forests” if accompanied by clearer steps at COP30 toward ending deforestation by 2030.

The destruction of tropical primary forest hit a record high in 2024, according to Global Forest Watch, a deforestation monitor. The equivalent of 18 football fields per minute was lost, driven mostly by massive fires.