Marriage market: How Jane Austen's England lives on in Pakistan's rishta culture

.jpg)

A group of brides pose for photographers at a mass marriage ceremony which organized by various non governmental organisations (NGOs), philanthropists and the Government of Punjab, in Lahore. (AFP)

The phone call comes at 9pm, after a long day at work. The man on the other end, introduced through her mother's WhatsApp network, is pleasant enough. 20 minutes in, he mentions that he can't cook. Or clean. His mother does everything, he explains, but of course after marriage, that would be his wife's responsibility.

"You'll still work, naturally," he adds. "We want a modern woman."

The woman, in her mid-20s, sits in her room and feels a familiar exhaustion. This is the third such call this week. Different men, same script: they want a working woman who will also shoulder all domestic responsibilities.

"This is not feminism," she says, recounting the experience weeks later. She requested anonymity to speak freely about family matters. "Feminism was meant to make our life easier, not harder."

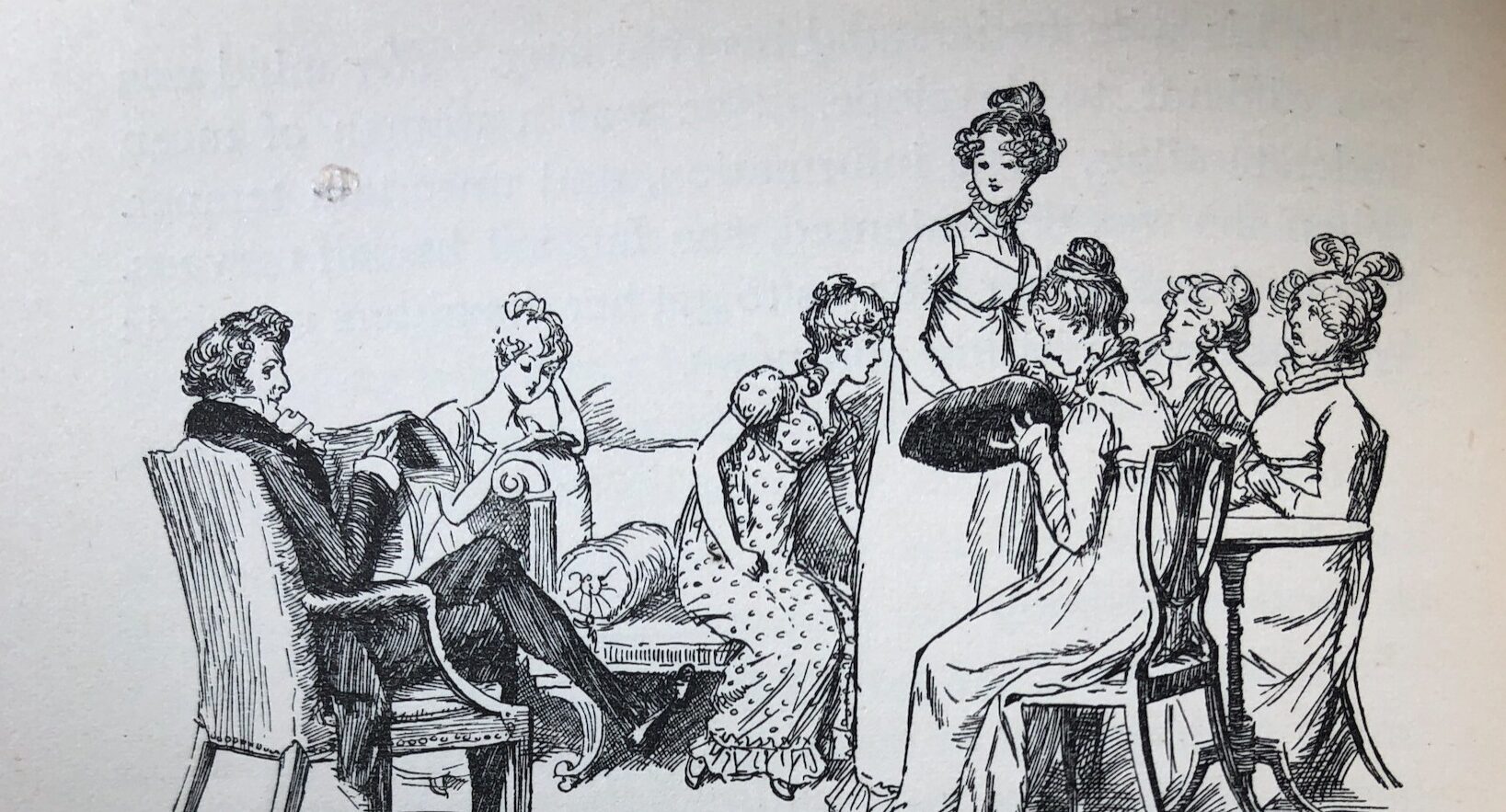

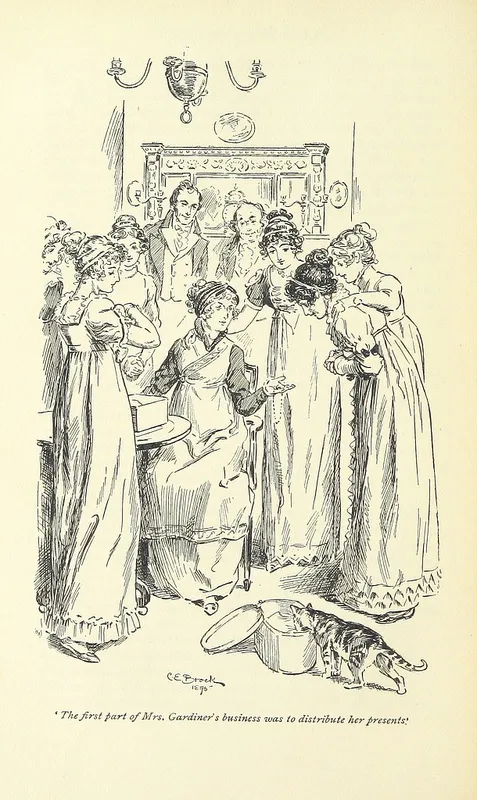

250 years ago, Jane Austen was born in Hampshire, England. The novelist would create some of English literature's most beloved characters: Elizabeth Bennet, Emma Woodhouse, Anne Elliot; women navigating the constraints of Regency-era marriage markets with wit and intelligence.

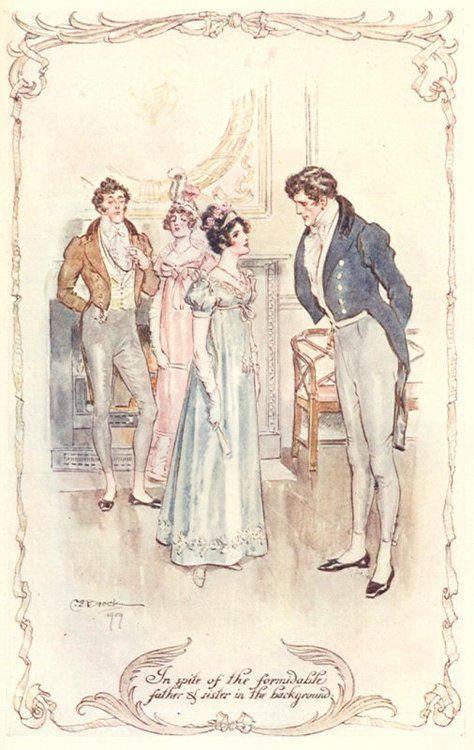

Austen's genius lay not in imagining escape from the system, but in documenting how intelligent women operated within it. Her heroines couldn't opt out of marriage, economic survival depended on it, but they could resist, delay and ultimately choose partners who offered genuine respect alongside financial security.

That tension between autonomy and constraint, individual preference and family pressure, remains startlingly alive in modern Pakistan. Here, the marriage market Austen satirized has evolved but not disappeared, migrating from drawing rooms to WhatsApp groups, from calling cards to biodata profiles.

Pakistan TV Digital spoke with four women who recently navigated or are currently navigating Pakistan's rishta system, the network of family connections and matchmakers through which most marriages are still arranged.

Their experiences, shared on condition of anonymity, reveal how Austen's observations about marriage as transaction rather than romance remain uncomfortably relevant.

Economics of eligibility

The woman, living in Islamabad, describes how proposals arrive: Her mother has joined numerous WhatsApp groups dedicated to matchmaking. When a man’s profile appears, it gets forwarded to daughters deemed age-appropriate.

"You don't even want to talk to them," her mother said after weeks of resistance.

She finally relented. What followed were conversations lasting one to two hours, mandatory auditions with prescribed questions. Do you pray five times daily? Can you cook?

In "Pride and Prejudice," accomplished women needed music, drawing, languages. Today's requirements are different but identical in spirit. Several families specified height requirements: between 5 feet 4 inches and 5 feet 6 inches. "My son is so tall, we want a girl that looks great next to him," mothers explained.

"Even if the guy had no prospects himself, he wanted a perfect wife: has to be religious and 'homely,'" she says. The word "homely" in Pakistani usage means domestically skilled, but the expectation is clear.

The cruelest irony, she notes, is that families explicitly want working women, dual incomes are increasingly necessary, but refuse to adjust expectations around domestic labor.

Unspoken rules

A Pakistani woman in her early 30s who holds a foreign passport but lives in Pakistan remembers when the pressure began.

"From an early age, since the teens, they were telling us to mentally prepare for marriage," she says. "Mind you, I was just 24 when the pressure intensified."

She resisted. Proposals came and were rejected. She became engaged once, then broke it off. Her parents, she says, "almost gave up on me."

In Austen's "Persuasion," Anne Elliot is persuaded at 19 to reject Captain Wentworth because he lacks fortune and connections. The novel's tragedy isn't that Anne made the wrong choice; it's that the choice was never truly hers to make. Family pressure overrode her own judgment.

Rare success

A 28-year-old woman based in Karachi describes a smoother experience, though one that still operated through the rishta infrastructure.

"My parents joined every WhatsApp rishta group on the planet," she says. She's currently working in the corporate sector and married two years ago. The proposal came through a family friend.

When asked how she knew he was right, her answer is simple: "I felt calm and comfortable with him."

"Marriage is not constant happiness, but long-term emotional safety and partnership," she says. "I believe the strongest marriages operate with a mindset of 'us versus the problem.'"

Darker edge

For a woman based in Peshawar who married in her early 20s, the process became traumatizing.

A proposal came through family friends. The prospective in-laws made their expectations clear: She would not be allowed to study further or work. "They earn enough to feed me," she recalls them saying. They openly discussed their wealth while explaining her economic contribution would be unnecessary.

Her family immediately rejected the proposal. Instead of ending there, it became a pressure campaign.

"They started insisting and started pressurizing my parents through our mutual friends to say yes," she says. The mutual friends became intermediaries, delivering messages about what a good match it was, how turning them down was insulting.

Persistent question

None of the women interviewed have given up on marriage. Like Austen's heroines, they're not revolutionaries attempting to dismantle the system. They're pragmatists trying to find decent outcomes within constraints they didn't choose.

"I'm not against arranged marriages," one told me. "I'm against the hypocrisy. Say you want a housewife, fine. Say you want a working woman who will also be your mother's replacement, that's honest at least. But don't dress up exploitation as feminism."

What strikes me most is how little has fundamentally changed since Austen's era. The mechanisms are more efficient, WhatsApp can connect families across continents instantly, but the underlying calculation remains: women as assets to be acquired, their worth determined by attributes that serve family interests.

The question Austen asked repeatedly was: Given that you must operate within this system, how do you preserve your dignity and autonomy? How do you find genuine partnership in a transactional market?

Elizabeth Bennet rejects Mr Darcy's first proposal and only accepts his second when he's demonstrated genuine respect. Anne Elliot spends years alone rather than settle. The women navigating Pakistan's rishta market are making similar calculations: seeking the same elusive balance between practical necessity and personal fulfillment.

Latest News

Russia resumes large-scale Ukraine strikes in freezing weather

38 MINUTES AGO

.jpg)

Balochistan attacks: UNSC condemns ‘heinous, cowardly’ terrorists

AN HOUR AGO

.jpg)

Son of Libya's late ruler Kadhafi killed by armed gang

3 HOURS AGO

Israeli army kills Palestinian man in West Bank as Netanyahu rejects PA role in Gaza

6 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

US-Iran talks 'still scheduled' after drone shot down: White House

6 HOURS AGO