In Islamabad, mosque school gives working children hope through education

ISLAMABAD: As dusk settles over the outskirts of Pakistan’s capital, the narrow lanes of a low-income settlement come alive with an unusual sight. Children, many still in the clothes they wore while sorting garbage or helping their parents at construction sites, file quietly into a small neighborhood mosque.

They leave behind the clatter of donkey carts and the metallic rustle of scrap yards, stepping into a space where the scent of incense mingles with the soft murmur of lessons.

Inside, the prayer hall doubles as a classroom. Woven mats become desks. Chalkboards lean against marble pillars. And the mosque, a place of devotion for generations, has become something else entirely: a refuge for children denied a place in Pakistan’s formal education system.

These students belong to the margins of Pakistani society, overage children, daily wage earners, and garbage collectors whose families cannot navigate the bureaucracy or costs of mainstream schooling. The national picture is stark: 26.2 million out-of-school children, according to government data, giving Pakistan one of the world’s highest rates.

Against that backdrop, the work of this community-run initiative stands out.

“We go door to door and tell parents about the importance of education,” said Farzana Naveed, a volunteer teacher, speaking to Pakistan TV Digital on Friday. “These kids are 8 to 12 years old. I complete their primary education in 2.5 years.”

“Our organization provides everything. Books, notebooks, pens.”

Her voice carries across the hall as she guides children through beginner English sentences. Some grip their pencils as if they are tools more unfamiliar than the metal hooks or sorting baskets they use at work.

While many mosques across Pakistan host traditional madrasas focused on religious learning, this initiative offers an entirely secular curriculum. Science, mathematics, social studies, and English are taught in an accelerated format designed to prepare students for placement in regular schools.

Attendance is remarkably high: 75–80 children arrive each day, often after finishing morning shifts.

The setting may be unconventional for international readers, but its logic is rooted in local realities. Mosques are familiar, trusted, and free, eliminating the barriers that keep impoverished families from sending their children to school buildings they cannot afford to reach.

Among the students is Hamza Khan, who spends early mornings picking through waste to supplement his family’s income.

“I couldn’t afford school before,” he said. “Now I collect garbage with my father in the morning, then come to school. So I can study and become an officer one day.”

His aspiration encapsulates a broader struggle in Pakistan, where 3.3 million children between the ages of 5 and 16 are engaged in child labor, including waste picking, brickmaking, and domestic work.

For many, education is not simply a dream; it is a distant luxury.

The initiative is run by the Junior Jinnah Trust, whose director, Muhammad Al Khyaam, believes this model can chip away at structural poverty.

“We’re breaking the generational poverty cycle by educating children doing child labor,” Khyaam said. “We open mosque schools within their communities to eliminate access barriers.”

By reimagining existing community spaces, the model sidesteps the costs and complexities of building formal schools. It also leverages the cultural role of the mosque as a trusted communal anchor, something particularly potent in under-resourced neighborhoods.

Pakistan’s literacy rate stands at about 60.6%, a statistic that reflects decades of inequality and underinvestment. Yet inside this small mosque classroom, the atmosphere feels almost defiant.

Children sit cross-legged under ornate calligraphy inscriptions, sounding out multiplication tables and practicing handwriting. Between their morning labor and their evening lessons lies a fragile but profound shift: the realization that they are allowed to dream.

They are not only learning to read or count. They are learning to imagine.

In this transformed prayer hall, where devotion has expanded into inclusion, education is more than instruction, it is liberation. And for the working children who gather here each day, it is the first step toward futures once written off by circumstance.

Latest News

Pakistani, European ministers agree on coordinated strategy to combat illegal migration

7 MINUTES AGO

UN approves first carbon credits under Paris Agreement

22 MINUTES AGO

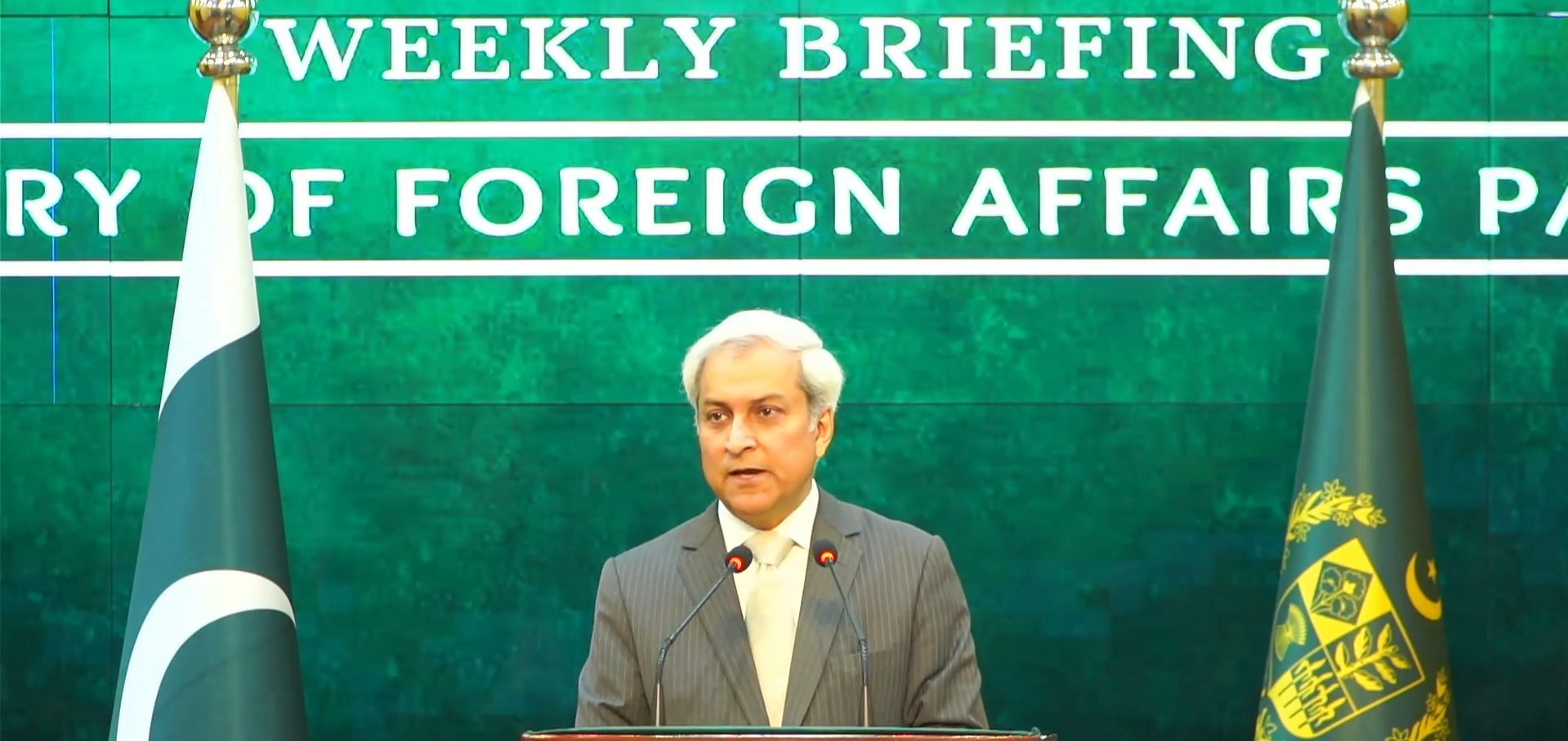

Pakistan to raise concerns over Israel actions in West Bank at OIC Ministerial: Foreign Office

AN HOUR AGO

Bangladesh to distribute 0.5M farmer cards in 180 days

2 HOURS AGO

.jpg)

Iran insists not seeking nuclear weapon ahead of US talks

2 HOURS AGO